Five years ago, I wrote a blog on the life of Josephine Baker and in particular, her resistance activities during World War II. Most of you probably have never read that blog so I decided to rewrite the blog in an expanded format along with additional images. However, there is another reason I decided to publish the “new” blog at this particular time.

Several weeks ago, President Emmanuel Macron authorized Josephine to be inducted into the Panthéon⏤only the French president can choose who enters the Panthéon. She is the fifth woman to be honored at this hallowed mausoleum for French icons and heroes. (A sixth woman is interned next to her husband who was inducted on his merits.) Click here to learn more about the Panthéon.

If this is your first introduction to Josephine Baker, I am confident that after reading her story, you will concur with President Macron’s decision.

Did You Know?

Did you know that while I lived in Holland, my favorite sodas were Fanta and Orangina? (Of course you didn’t know that.) My mother used Fanta syrup to create the soda drink while I consumed Orangina from a little cardboard box with a straw. When I visit Europe, my choice of non-alcoholic beverage is either Fanta or Orangina. Even today, Fanta is very well-known around the world but not so much in the United States.

However, the real “Did You Know” question is whether you knew that Fanta was developed by Coca-Cola in Nazi Germany. Demand for the company’s products was very low outside the United States and in 1923, the CEO decided to expand Coca-Cola’s international presence. He set up bottling plants in twenty-seven countries and supplied the flavoring (each country provided the bottling equipment and sugar). One of the countries that “won” a Coca-Cola bottling contract was Germany. The man in charge, Ray Rivington Powers, was responsible for increasing sales from six thousand cases a year to more than 100,000 cases. He was a great salesman but his bookkeeping skills were sloppy and that got him into trouble.

Almost concurrent with Adolf Hitler’s takeover of the German government in 1933, Max Keith came on board with Coca-Cola and saved the German subsidiary from ruin. He also heavily marketed the brand and began to convert the soda’s reputation from an all-American product to one that was fit to drink by the German consumer. Coca-Cola became one of the major sponsors of the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics. The company’s logo was seen next to the swastikas, on trucks at Hitler Youth rallies, and at the end of one of the annual conventions, Keith led a pledge to Coca-Cola followed by vigorous “Sieg heil” salutes to Hitler.

After the United States entered World War II, a full embargo on Germany was enacted. The German subsidiary was forced to cut all ties with the American company and the flow of Coca-Cola syrup was immediately halted. Keith was forced to develop an exclusive German soft drink. His new drink was made with leftovers from other food industries, mostly scraps from produce markets (e.g., fruit pulp, apple fibers, and whey). The drink was named Fanta and it was the only product Keith had to offer. Fortunately for him, there were no other competitors at the time and the demand for Fanta exploded.

As a result of his Third Reich connections, Keith consolidated his business to all Coca-Cola plants in Germany as well as the occupied countries. After Germany was defeated, the production of Fanta ceased and Keith turned all profits over to Coca-Cola in Atlanta, Georgia. What we know today as Fanta Orange was developed in Italy around 1955. The liquid was a bright orange (the original soda was a similar color as ginger ale) and used only orange scraps.

As part of Coca-Cola’s seventy-fifth anniversary in 2015, the company advertising used “The Good Old Times” to reference the period in Germany during the Third Reich. International backlash forced Coca-Cola to withdraw the ads and issue an apology. They said, “The 75-year-old brand had no association with Hitler or the Nazi party.” I’m not too sure that statement is entirely correct.

Most of us have never experienced blatant discrimination because of our skin color. Every country can point to episodes in its past that are regrettable and if possible, its citizens would certainly jump at the chance to turn the clock back and try to undo the damage. For America, I think most of us would agree that slavery was our low point. Even after the Civil War and emancipation, the Jim Crow laws of the south (and let’s not totally exclude the north) prevented African Americans from exercising their rights. Before the civil rights movement of the 1960s, entertainers such as Sammy Davis Jr., Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald, and Nat King Cole were not allowed to stay in Las Vegas hotels (in other words, you can perform here—to segregated audiences—but you can’t stay here). Our story today is about an African American entertainer who moved to Paris during the Jazz Age because her talents were recognized and appreciated by the French. Unlike America, the welcome mat was always out for her to stay at the French hotel of her choice. By the end of her life, Josephine Baker was hailed not only as one of the world’s top entertainers but also a World War II French Resistance hero and one of the leaders of the American Civil Rights movement.

Freda Josephine McDonald AKA Josephine Baker

Josephine Baker (1906–1975) was born into extreme poverty in St. Louis. By the age of eight, her mother began to hire out Josephine as a live-in maid. One of her memories was being abused and punished if she made eye contact with her white employer. Five years later, Josephine was living on the streets and dancing on the street corners to make money (similar to the waifs in Paris—think Edith Piaf—who sang on the street corners in the early 1900s).

Josephine married the first of her four husbands when she was thirteen. At fifteen, she divorced him and married Willie Baker. Although divorcing Willie in 1925, she decided to keep his name as her audiences were beginning to recognize Josephine Baker as a top performer and dancer in the entertainment world.

Paris and Heartbreak

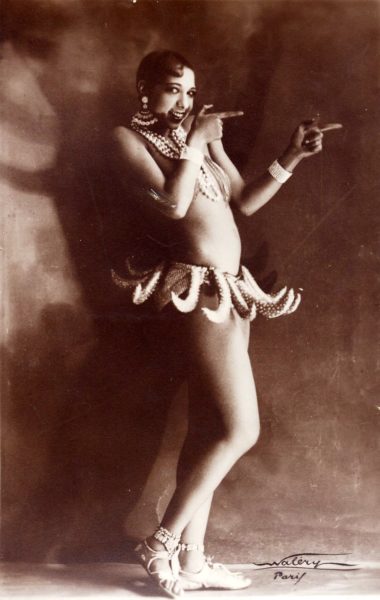

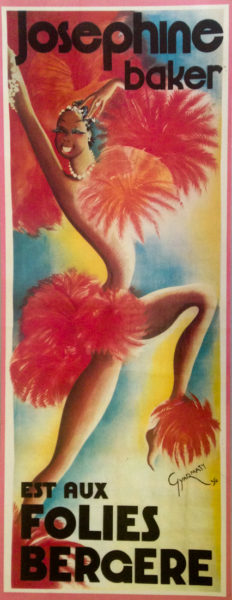

In part to get away from her mother, Josephine left for Paris in 1925 at the age of nineteen. The world was caught up in the Jazz Age and the Roaring Twenties. Four years later America (and soon the world) would enter the Depression era. In the meantime, Josephine quickly became a celebrity with the Parisians. Her first gig on 2 October 1925 was La Revue Nègre. She became known for her erotic dancing including appearing practically naked on stage wearing only the famous banana skirt. After a successful tour of Europe, Josephine returned to Paris where she began a long engagement at the Folies Bergère nightclub. She was the first African American to star in a motion picture: Zou Zou (1934). By this time, Josephine had expanded her skills to include singing and comedy. Click here to watch Josephine perform.

Josephine returned to the United States in 1936 for the purpose of starring in the revival of the Ziegfeld Follies. Despite her success and popularity in France and Europe, American critics trashed her performance. This experience hurt her tremendously and when she returned to Paris in 1937, Josephine renounced her American citizenship, married her third husband, and became a French citizen. Click here to watch the video My Fate Is In You Hands-Josephine Baker-1929.

French Resistance Agent

Immediately after declaring war on Germany in September 1939, the French military organization known as the Deuxième Bureau recruited Josephine as an agent. Because of her celebrity and need to travel, Josephine gained access to many embassy parties, rubbed shoulders with the highest military officers, and other assorted German officials. She was able to learn about troop movements and locations, both of which she passed on to her intelligence handlers.

After the Germans invaded France and created the Occupied Zone, Josephine left Paris and moved to the south of France to live in her home, the Château des Milandes. Using this as her base, Josephine began to assist the French Resistance. Her celebrity status allowed her to move around Europe with relative ease. She began to assemble information concerning airfields, harbors, and German troop movements. Josephine would write her notes using invisible ink and hiding them in her sheet music. This information would then be transmitted back to London to Charles de Gaulle and the Free French.

Her work for the resistance movement was rewarded with Josephine’s appointment as a lieutenant in the Free French Force. After the war, Josephine was awarded the Croix de guerre and the Rosette de la Résistance. In addition, General de Gaulle bestowed upon Josephine the prestigious Chevalier of the Légion d’honneur.

Back to the United States

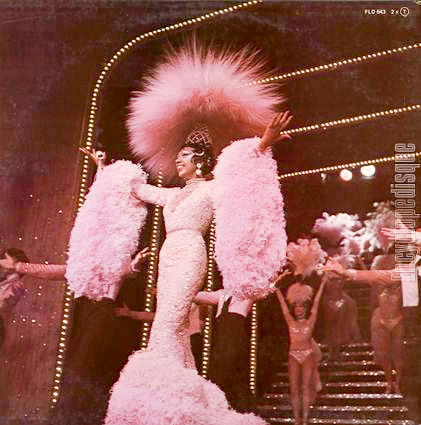

After the war ended, Josephine returned to Paris and the Folies Bergère. Now, not only was she a top entertainer, but Josephine was also a recognized French war hero. At about this time, the French fashion industry was in disarray. Once they discovered Josephine’s talents for design, the top fashion designers turned to her for help in creating postwar fashions. She is credited with saving the Paris fashion industry immediately after the war.

Josephine was invited back to the United States in 1951. This time, she got great reviews and was given a wonderful parade in Harlem, New York. The NAACP honored her with the title “Woman of the Year.” Unfortunately, the warm and fuzzy reception did not last long.

She and her husband were refused reservations at thirty-six hotels in New York City due to her skin color. A night out at the famed Stork Club was the catalyst for her move back to Paris. She had been refused service at the club and she criticized their unwritten policy of discouraging African American patrons (Grace Kelly witnessed this episode and came to her defense). After her good friend Walter Winchell (soon to be ex-friend) refused to support her stand against the Stork Club, he began to write accusations that Josephine was a Communist (remember, this was the McCarthy era—another sad episode in our history). This resulted in the cancellations of Josephine’s engagements, and she returned to Paris once again, heartbroken.

It would be ten years before she would be invited back to the United States.

The Civil Rights Movement

Josephine experienced racism her entire life while living in America and on her subsequent returns. She refused to perform at any venue that required segregated audiences. Once while in Las Vegas, Josephine sat down on stage and refused to perform until the hotel permitted African Americans to purchase tickets and attend her show. Josephine is credited today with helping to desegregate Las Vegas casinos. (Frank Sinatra would refuse to perform anywhere unless the venue owners treated Sammy Davis Jr. as an equal.)

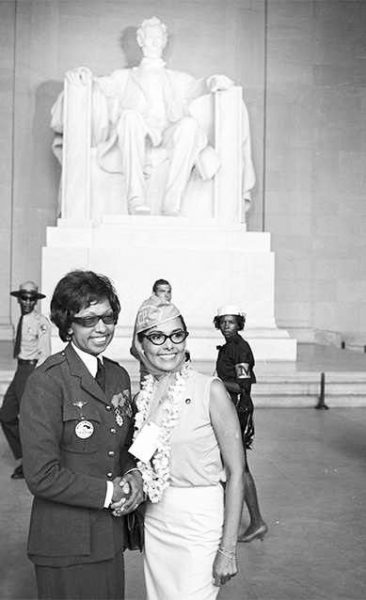

Martin Luther King Jr. invited Josephine to be the only female speaker at the March on Washington in 1963 (she proudly appeared in her French uniform). Josephine was given a life membership in the NAACP in recognition of her efforts. After Dr. King’s assassination, his widow, Coretta Scott King, reached out to Josephine and asked her to take over her late husband’s role as leader of the Civil Rights Movement. Josephine declined saying her twelve children were “too young to lose their mother.”

The Rainbow Tribe

Josephine never had any children of her own. She opted to adopt twelve children: two daughters and ten sons. The children were from France, Morocco, Korea, Japan, Colombia, Finland, Israel, Algeria, Ivory, and Venezuela. She called her children “The Rainbow Tribe.”

The children grew up at the Château des Milandes and accompanied their mother throughout Europe. Two of her sons, Jarry and Jean-Claude, went on to run a highly successful New York City restaurant called Chez Josephine. Appropriately, the restaurant is located on Theater Row and the décor highlights their mother’s career. Click here to learn about Chez Josephine.

Josephine’s Legacy

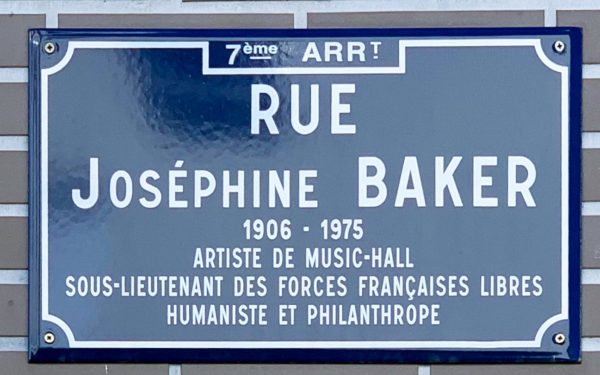

Paris has honored Josephine’s legacy by naming the Place Joséphine Baker in the Montparnasse Quarter (14e). A swimming pool located along the banks of the Seine in Paris is also named after her. The Château des Milandes is now open to the public and houses Josephine’s various stage garments (including the famous banana skirt) along with her medals and family photographs. Angelina Jolie has said that Josephine was her role model for the “multiracial, multinational family.” Click here to learn more about visiting Château des Milandes.

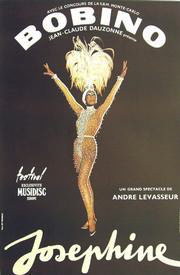

Josephine lost her French home due to unpaid debts. Her friend, Princess Grace (Kelly), gave Josephine an apartment in Monaco. On 8 April 1975 in Paris, Josephine starred in a revue based on her 50-years in Paris entertainment. Anyone who was anybody attended. Four days later, Josephine died of a cerebral hemorrhage at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital and was buried in Monaco dressed in her full uniform.

Le Monocle Nightclub

Josephine’s sons have written their mother was bisexual. During the 1920s and 1930s, a lesbian nightclub called Le Monocle was popular in the Left Bank of Paris. I’ve included an image of Josephine sitting in a racecar with Violette Morris. Violette was one of the more infamous patrons of the nightclub. As one of our blogs pointed out, Violette was a notorious Nazi collaborator. So, I’ve always wondered if Josephine met Violette at Le Monocle and I thought it ironic that the two women were sitting side by side in a car—one a future Nazi collaborator (executed by the resistance) and the other, a future French Resistance agent (revered by the French). Click here to learn more about Le Monocle.

African American Ex-Pats in Paris

Josephine Baker was not the only African American ex-pat performer in Paris—only the most famous. There were many African American performers who moved to Paris between the two world wars. Although each probably had their individual reasons, the common thread I suspect was escaping America’s racism and Jim Crow.

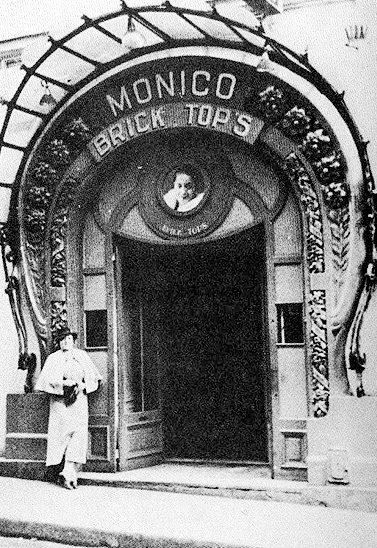

The hub of activity for the African American performers was the nightclub Chez Bricktop. Ada Smith (1894-1984) aka Bricktop opened the nightclub in 1924 and over the next forty years, owned and operated similar clubs in Mexico and Rome. A performer herself, Ada continued to perform well into her eighties. Click here to watch a video clip on Chez Bricktop.

Chez Bricktop hosted celebrities such as Cole Porter (he hired Ada to entertain at his parties as well as financed the start of her club), the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others. During this time, Ada mentored Josephine Baker (her sons wrote the two had a relationship together in the early days), Duke Ellington, and Mabel Mercer. Cole Porter’s song “Miss Otis Regrets” was written specifically for Ada. I hope you enjoy this 1934 rendition by Ethel Waters. Click here to listen.

I also happen to like the version by Bryan Ferry.

The Panthèon

President Macron announced Josephine would enter the Panthéon on 30 November 2021. This is the month and day she became a French citizen. Josephine is the first African American and first entertainer to be inducted into the Panthéon. Her remains will not be moved from her Monaco grave. A commemorative plaque will be erected inside the Panthéon.

★★ Learn More About Josephine Baker ★★

Atwood, Kathryn J. Women Heroes of World War II. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2011.

Baker, J.C. & Chris Chase. Josephine: The Hungry Heart. New York: Random House, 1993.

Baker, Jean-Claude & Chris Chase. Josephine: The Josephine Baker Story. Avon: Adams Media Corporation, 1995.

Glass, Charles. Americans in Paris: Life & Death Under Nazi Occupation. London: Penguin Books, 2009.

Jules-Rosette, Bennetta. Josephine Baker in Art and Life: The Icon and the Image. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2007.

Nissotti, Arys (Producer). Zou Zou. Produced by Les Films H. Roussillon and Productions Arys, 1934.

Sharpley-Whiting, T. Denean. Bricktop’s Paris: African American Women in Paris between the Two World Wars. Albany: SUNY Press, 2015.

Disclaimer:

There may be a chance that after we publish this particular blog, the video links associated with the blog are no longer accessible. We have no control over this. Many times, whoever posts the video has done so without the consent of the video’s owner. In some cases, it is likely that the content is deemed unsuitable by YouTube. We apologize if you have tried to access the link and you don’t get the expected results.

What’s New With Sandy and Stew?

I had to stop the presses when I read that President Macron was going to induct Josephine Baker into the Panthéon. So, I pushed out the scheduled blog for 11 September (today) to 25 September to give you this expanded version of my previous blog on Josephine. The rescheduled blog is about Saint-Germain-en-Laye (fascinating history), German military headquarters, and the bunkers constructed in the village. It is one of the “Métro Walk” stops in the soon-to-be published book (first volume), Where Did They Put the Gestapo Headquarters? A Walking Tour of Nazi-Occupied Paris. I hope you will enjoy the sneak preview into the book.

Thank you to all of you who subscribe to our bi-weekly blogs. It seems there isn’t a day that goes by where we don’t increase our readership. Please let your history buff friends and family members know about our blog site and blogs.

Someone Is Commenting On Our Blogs

I’d like to thank Pat V. (again) for her comments about our blog, Camp King. She says, “Always an interesting day when your blog arrives.” Thanks Pat. (Click here to read the blog.)

If there is a topic you’d like to see a blog written about, please don’t hesitate to contact me. I love hearing from you so keep those comments coming.

Why Would You Want to Buy Our Walking Through History Books?

Simple.

You like to travel and experience history and historical events. You like to see original buildings that had a significant impact on the people and events of the history you’re engaged with. You want to know the stories behind the brick and mortar in front of you.

The walking tour books are meticulously researched so you can go directly to those sites and learn about the building’s history as well as an introduction to some of the more interesting people associated with it.

We Need Your Help

Please tell your friends about our blog site and encourage them to visit and subscribe. Sandy and I are trying to increase our audience and we need your help through your friends and social media followers.

Thank You

Sandy and I appreciate you visiting with us. We have some exciting things on the horizon, and we’ll keep you updated as we go along.

Share This:

Follow Stew:

Find Stew’s books on Amazon and iBooks.

Please note that we do not and will not take compensation from individuals or companies mentioned or promoted in the blogs.

Walks Through History

Walks Through History

Copyright © 2021 Stew Ross